A. Connors on The Girl Who Broke the Sea and thrillers for young readers

The books we chose for our Macaw subscribers this month are both thrilling mysteries with strong ecological themes and a lot to say about the role of technology in our lives. We were completely gripped by The Girl Who Broke the Sea. Lily's story is thought-provoking and in places very unsettling, but ultimately fascinating and hopeful. The book says so much about friendship, self and our sense of home and we know young readers are going to love it. Author Adam Connors tells us about being inspired by the deep-sea and which thrillers for young people he recommends you turn to next.

What inspired you to write The Girl Who Broke the Sea?

A bunch of things just sort of came together.

I started with Lily, my main character. I knew she didn’t really fit in, I knew that on the inside she was smart and resourceful and sharp-witted, but that for some reason, on the outside, she just came across as somebody you’d dismiss as a “troubled teenager”. User-interfaces and communication is a big theme in the book, and I got caught on this phrase: humans have rubbish user interfaces.

I also knew that I wanted the break-up of her parents, and the move that it necessitated, to be part of her backstory and her entry point into the book. So then I was just looking for the right setting, somewhere that Lily would absolutely hate!

I hit on the idea of a deep-sea mining rig because one of my friends is an ROV driver (Remotely Operated Vehicle, think mini-sub) and it just seemed perfect. Cramped, stuffy, smelly, noisy. Everything Lily is not good at.

As soon as I started researching the deep-sea (specifically the Abyssal Plains, vast flatlands 5 km below the surface) it just kept getting more and more interesting. I spoke to a bunch of oceanographers and there was a sense that we just don’t really think about the deep-sea enough. We’re “land dwelling mammals” as they put it, and biassed to care more about the land than the deep-sea. And that’s a problem because we still know so little about it. The scientists who work down there say that they discover something entirely new to science every time they visit. But at the same time there is increasing pressure to start commercial mining of the seabed. If industry is allowed to strong-arm science, we could destroy entire ecosystems without ever knowing they existed.

So by this point I had a troubled girl with a lousy user-interface, a world that’s actually very real, and grounded, and close, but also utterly different to our everyday experience, and a tense standoff between science and industry. All I needed was for Lily to find something down there … something dangerous, but also wonderful.

Are any of the characters or elements of the story based on real people or events?

I stole some of the names of my colleagues at work and one of my son’s teachers, but the characters are actually not related at all — I just liked the names. It was kind of weird, after it got published, I had to give a couple of colleagues a heads up that I’d stolen their names so they wouldn’t be surprised!

The scientific aspects of the story are based in reality. They’re a little bit ahead of where technology is now, but the basic physics is plausible. I used to be a physicist, I care about stuff like that.

What do you hope young readers will take away from the story and how it unfolds?

One of the recurring themes in the book is communication. Human to human communication; human to computer communication; human to vast unknowable deep-sea intelligence communication. The person we are inside, the person we present to the outside world, and the gap in between.

People are complex and messy, and our first impression of somebody is never going to be completely accurate. We need to be more forgiving of each other, and ourselves, and try harder to see the world through each other’s eyes.

Do you think the grown-ups in the story behave fairly towards the young people? What, if anything, could they have done differently?

Actually, kind of, yes. I was quite keen not to write a story that relied on a stereotypical “bad guy” or “evil stepmother”. All of the grown-ups in Lily’s life are pretty reasonable people, but they all have their own limitations and failings that sometimes get in the way of them doing the right thing.

Carter, the rig boss, is the closest I have to a “bad guy”. His values around meeting his quotas and making money for the mining companies are the most misaligned with the values of the book. I guess the point where he tries to blow Lily up was kind of unfair, but I still have a certain amount of sympathy for him.

Can you tell us anything about what the future holds for Lily?

There’s a huge amount of open questions at the end of the book in terms of what Lily has found and how that relationship might evolve in the future.

How does it think? What does it understand? It’s an intelligence, but its experience of the world is so profoundly different from our own. It’s billions of years old, but it’s also brand new: a moody toddler; a stroppy teenager.

I don't think we can make any assumptions about how it will respond to any given situation, and I think that’s going to cause an awful lot of trouble for Lily.

Why did you choose to write books for this age group?

Books have always been a huge part of my life. But I remember the books I was reading through my teens and early twenties more vividly than any others. It’s a period in life when there’s so many firsts, but it’s also a period that can feel a bit rubbish at times.

Books are important, because they help to guide us towards what is worth noticing in the world. What, of all the vast cacophony of things vying for our attention, is meaningful, and worthy of our brain.

In my teens I was hungry to live and experience more things, and figure out more about myself and the world and other people. Books can be a great way to short-circuit some of that process by injecting you into other worlds and other people much more quickly than you can do by hand.

So it just felt natural to want to write to an audience that was in the midst of that tremendously exhilarating, terrifying, irritating period of life.

Do you have a favourite place to write?

I wrote a lot of this book during my morning commute on the train. It should be a rubbish place to work, noisy and stuffy, butting laptop screens and knees with the person opposite you, but that constrained 40 minutes twice a day really helped with my focus. I think it’s a bit like doing a sport, you have to write every day (or as near to it as you can get) so that writing becomes a habit and your body wants to do it. For me, that twice daily train journey gave me the rhythm and certainty I needed to ensure that I wrote regularly, and it’s the regularity that allows the story to stay alive and grow in your head between each sitting at the laptop.

Which other thrillers for this age group would you recommend our subscribers read next?

My absolute favourite series of books is the Scythe trilogy by Neal Shusterman. They’re a little more intense than The Girl Who Broke The Sea and maybe slightly older. But so, so good. The ideas kind of stick in the brain and change the way you think, and the world is similar to The Girl Who Broke The Sea, in that it’s not quite now, but also not so far away either.

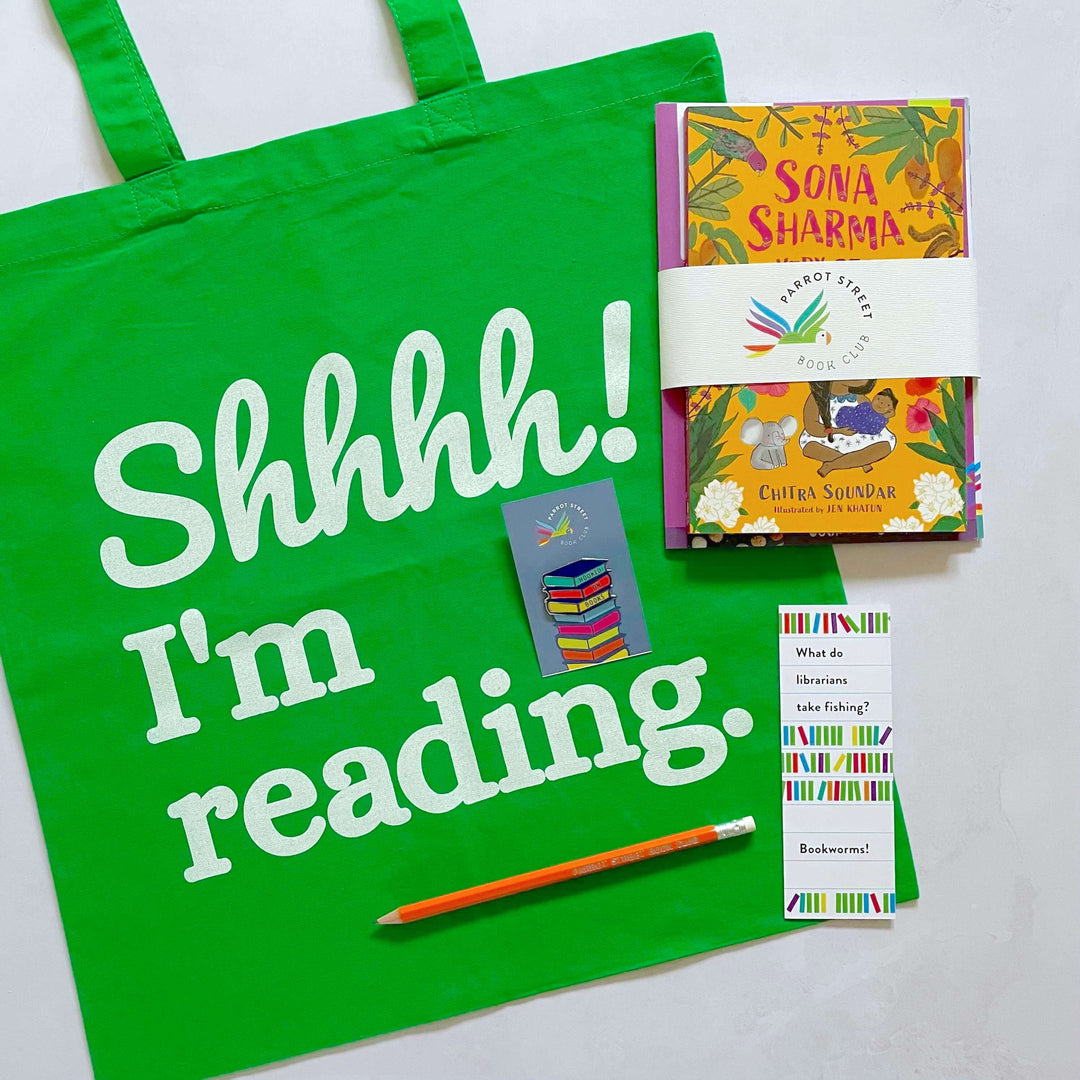

Copies of our The Girl Who Broke the Sea pack, including a copy of the book and loads of fun activities to go with it, are now available for individual purchase. Grab a copy while stocks last!

This post includes affiliate links to our bookshop.org page, meaning we receive a small percentage of the sale should you purchase through them. Additionally, a percentage from all sales on the platform goes directly to local UK bookshops which is an initiative we're delighted to support!

JOIN OUR EMAIL LIST

Children's book news straight to your inbox

We love sharing product updates, book recommendations, children's activity ideas and special offers via email.